Lessons From Running an Open Source Community Project

I spent a little time this weekend tidying up the GitHub repository for Exchange Analyzer, a project that I was leading and contributing to, and that has now ended feature development. If you want to know more about Exchange Analyzer itself, please visit the project website.

In this blog post, I want to share what I learned from over a year of working on an open source community project.

Projects Need a Purpose

Whether you’re starting a project or creating a product, it’s important that it has a real purpose. That purpose could be solving a problem, teaching a skill, or just providing entertainment.

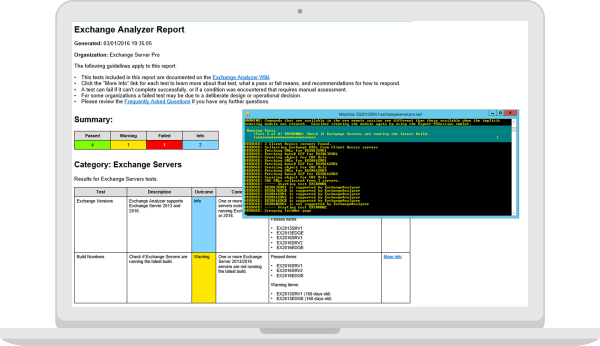

Our project aimed to solve a problem by providing a tool that analyzed Exchange Server environments for compliance with best practices. Traditionally, Microsoft provided a best practices analyzer (BPA) for each new version of Exchange. But they stopped after Exchange 2010, likely due to development efforts and budget focusing on their Office 365 cloud services instead.

Many of my fellow Microsoft MVPs were hearing from customers wanting a BPA for newer versions of Exchange to help keep their deployments healthy and aligned with best practice. After some email discussions, a few of us decided to create one ourselves.

Projects Need Leaders

Without leadership, a project will stall and make very little progress. Leadership doesn’t need to be an individual. There are many community projects that have leadership teams or committees, with a set of rules for how decisions are made. But whether it’s an individual or a team, leadership is what keeps a project moving forward.

In future, project leadership is something I will look at early on. For an individual, you are the project leader. If your project grows, I’ve learned that it’s helpful to bring on additional help with clear, defined roles.

Incremental Progress is Better Than No Progress

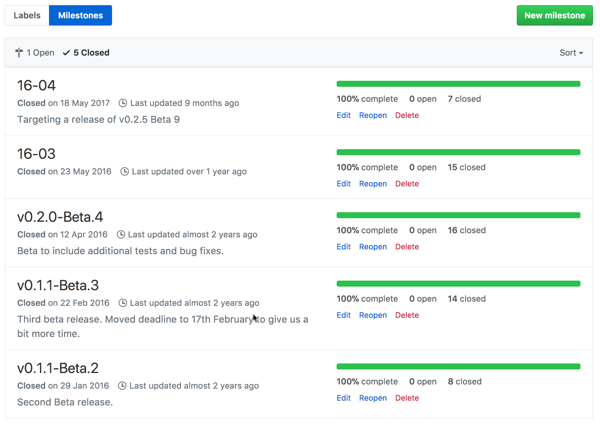

At first we ran the Exchange Analyzer project with ad-hoc releases. When this became unwieldy, we started to create project milestones with agreed deliverables. The deliverables were either features that had been chosen for the next release, or fixes for bugs in existing features.

Having milestones helped to focus our attention rather than just pick tasks at random.

Think Big Early

The proof of concept I wrote for Exchange Analyzer was a single script file. After that initial version, we quickly realized that maintaining a monolithic piece of code was going to be messy, if not impossible. I have some very old scripts that have become almost unmaintainable due to poor design decisions early on.

So, we spent some time at the beginning of the project making it more modular. Almost a framework, although I’m not sure that’s the correct word for it. Ultimately it meant that each individual test that Exchange Analyzer performed on an environment was a self-contained, standalone piece of code, that then fed test result data in an agreed format for another component to ingest and turn into report data. This scaled pretty well as we added more tests, and it’s one of the things I’m most proud of.

Later, another piece of code was developed to better handle data that needed sharing between multiple tests. This also solved scaling and performance problems, and we even began to retrofit it to earlier components.

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned from this project is to think big early on, and make simple architecture decisions that will scale. You can do this without over-engineering things, and you’ll thank yourself later.

People Get Busy

The number one problem we faced with Exchange Analyzer was a shortage of time. When the idea first came about, I spent a few days during my vacation time just hammering out the code for a proof of concept. Once that was up and running, and architectural improvements were made, there were a few more sprints to get the very first public release done.

After a period of heavier work early in 2016, other work commitments came up that took priority. You can see my contributions dropped off late in 2016, and although I was able to spend some reasonably consistent time in 2017, it never returned the level of those early days.

Other project contributors had similar ebbs and flows. Ultimately I think this project just doesn’t align with our professional commitments today the way it did at the beginning. It’s hard to keep selflessly working on a community project that isn’t returning any real benefit to yourself.

It’s probably also fair to say that early in a project the contributors’ enthusiasm will exceed their availability. This is something that project leadership needs to manage. For future projects, I would consider simple measures such as:

- Writing better code standards/guidelines. We developed ours over time and had to reject some early pull requests as a result.

- Marking bugs or issues as “first-timers” or “good-first-bug” as a way to direct contributors to a starting point.

- Limiting contributors to a single issue at a time, to avoid them over-filling their plate with assigned tasks or issues that they can’t deliver on.

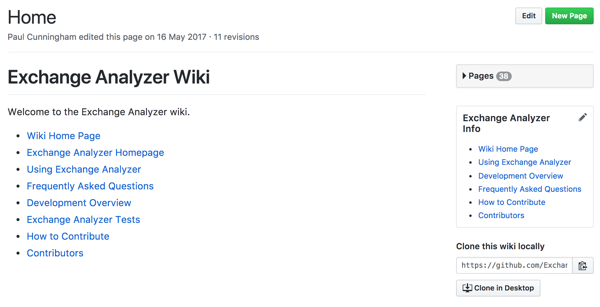

- Requiring documentation or wiki pages to be written before accepting a pull request, to solve the problem of the code base growing without supporting documentation.

I’ve struggled a little with those points. Sometimes I feel they are too discouraging, and could harm a project. Other times I’ve felt they were fair, considering some of the strict requirements that larger open source projects have for contributions. I am comfortable with them for now, and would at least test them on my next project to see whether they are helpful or not.

All Contributions Provide Value

In our project we had people contributing ideas, architectural advice, code, peer review and testing, feature requests, bug reports, and documentation. All those contributions were valuable and helped the project to make progress.

In the past I’ve often looked at open source projects and thought I had nothing to add unless I could contribute code. But now I see that even the simple act of improving a project’s documentation would be a good contribution.In fact, considering how busy everyone is with their day jobs, families, and life in general, any contribution to an open source project should be appreciated. It’s opened my eyes to how I can be more involved in others’ projects, and how I can welcome more contributions to my own projects in future.

Tools Don’t Magically Solve Problems

One of our challenges was peer review for code contributions. Without peer review, there was the risk of bad code making its way into a release. The main problem was time. Contributors were already short on time, and adding the burden of peer review to the mix was slowing us down even further. We tried to solve the problem by adding a tool to the mix, Reviewable.io. It worked from a review perspective, but didn’t solve the issue with lack of time. In fact, it probably added friction to the process because now we needed to learn another tool.

That said, GitHub is excellent. We moved Exchange Analyzer out of my personal GitHub and into an organization account early on, before it was publicly released. That solved some permissions/rights issues that I couldn’t quite grasp with a personal repository. I wouldn’t try to run any collaborative project without GitHub today. That’s my personal experience, and perhaps other source control and collaborative platforms are very good as well, but I am a fan of GitHub for sure.

Projects Can End

Nothing lasts forever. When a project has reached the end of its usefulness, or you simply don’t have time to invest in it any more, it’s okay to let it go. In fact, it’s healthy to do so. Unfinished business holds us back. Constantly being reminded that you haven’t updated a repo, or dealt with that bug report, uses up energy and brain cycles that are better spent elsewhere.

Don’t be afraid to close the book on a project and move on, as I’m doing with Exchange Analyzer.

I’m Sold on Open Source

As someone with a Microsoft IT pro background, you would be forgiven for thinking I am against open source. In fact, I have no problem with open source. It just happens that my career has been in the Microsoft space, since that’s where I started and is where my growth opportunities were.

Once I reached a level of proficiency where I felt comfortable sharing my code, I started publishing it online. At first I used my own website to share scripts for download, and then started using GitHub. I’ve spent the last few years adding code to my GitHub account and “coding in public” as much as possible. There’s two reasons for this:

- I want to be transparent and invite collaboration for my own benefit. I’ve learned a lot from issue reports and pull requests that others have sent me.

- I want my code to be useful to others long after it is no longer useful to me. Many of my repos are unmaintained as I simply don’t have a personal need for them any more. But at least my code is out there for others to continue using.

So, I’ve definitely got nothing against open source. Today I’m contributing as much code as I can to the public, and hopefully more in future.